Gauging and weighing the impacts of oil and gas development

AirWaterGas provides unbiased research for use in education, regulations

By Cathy Beuten | CU system

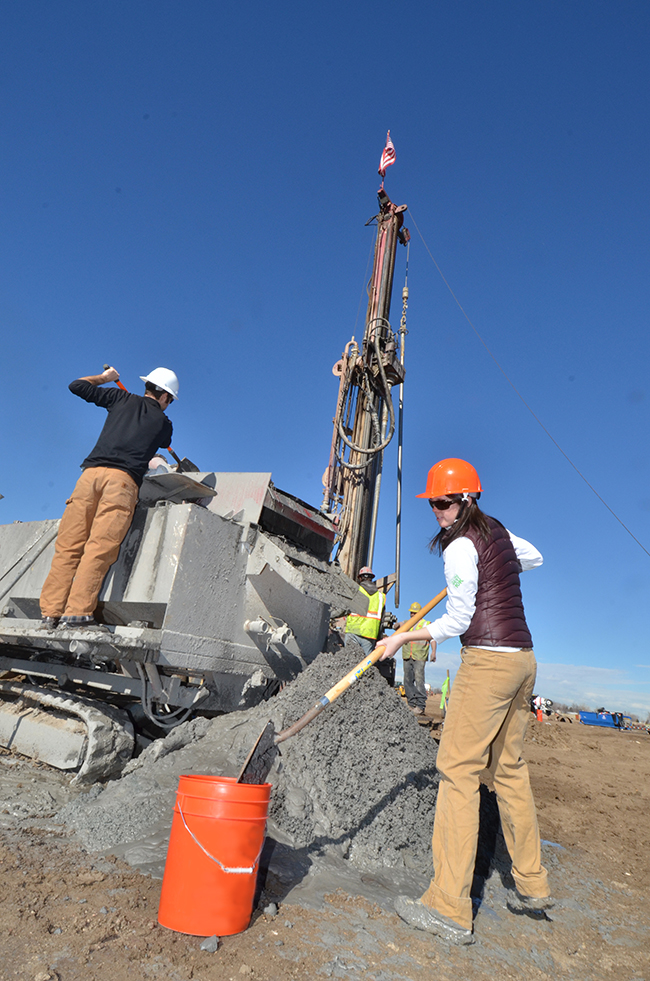

The AirWaterGas Sustainability Research Network at CU Boulder was initiated in October 2012 to help answer these pressing questions. The project aims to get more science into decision-making about oil and gas regulations and practices; and to provide an unbiased source of information about the benefits, risks and costs of oil and gas development.

With funding from the National Science Foundation, Joe Ryan, professor of civil, environmental and architectural engineering, Mark Williams, professor of geography, and Mike Hannigan, professor of mechanical engineering, in 2012 assembled the network that enlists experts from throughout Colorado – including members from CU Denver, the Colorado School of Public Health, Colorado State University and the Colorado School of Mines – and as far away as the University of Michigan and California State Polytechnic University.

One prominent example of research undertaken by the network is the determination of the setback -- the distance between an oil and gas well and occupied buildings. “The issue was what the setback distance should be between a new oil and gas well and existing residential buildings or occupied buildings -- it could be a school or hospital or an office as well as a home,” Ryan explained. “Basically, you have opposing sides – the oil and gas industry would like it shorter so they could have freedom to drill where it’s geologically best and best for profits, and you have the people who have the well near their back yards and would like it farther away.”

There had been no use of any kind of science to lead to an assessment of public health or how changing this distance would affect the oil and gas industry, he said. The network is working to incorporate data it has collected, such as air quality, water quality and noise, and also data that has been collected by other sources.

“It’s a way of trying to put all of this information together to consider how these different effects would matter for what the setback distances should be.” The effort is being led by Joseph Kasprzyk, professor of civil, environmental and architectural engineering.

“We want to make sure they know what kind of information is available and provide some sort of tool to help them incorporate information of different types on a properly weighted basis,” he said. For example, if you have air quality data that says the well should be farther away, but you have economic data that says the county will benefit by having more drilling, “How do you weigh the opposing information? That’s what we’re working on.”

The AirWaterGas network includes 27 scientists and researchers from nine institutions working in teams to explore the project’s main research interests.

“Our team is diverse, with a range of scientists from a variety of backgrounds including geography, law, petroleum engineering, political science, public health, engineering and more,” Ryan said.

Although each participant works on individually, researching a particular set of questions, the network has created avenues for cross-disciplinary interaction including all-network meetings and a variety of other smaller gatherings among team members. In addition to faculty, a number of graduate students are working on the project, gaining valuable work experience and being mentored by team members, Ryan said.

The project comprises nine teams:

- Air Quality

- Water Quality

- Water Treatment

- Water Quantity

- Oil and Gas Infrastructure

- Social-Economic Systems

- Health Effects

- Education and Outreach

- Practices and Policies

When the team members initially presented the research proposal to the NSF, they determined they would focus on the Rocky Mountain region. “And then we focused even more, mostly on Colorado because it turns out Colorado is a great laboratory for this kind of study,” Ryan said.

Colorado has four major oil and gas basins of three different types that represent the variety of basins found nationally. One of these basins is the Denver-Julesburg Basin in northeast Colorado. Even though drilling has slowed quite a bit in the past year, the Denver-Julesburg Basin is still the epicenter for most of the activity, Ryan said.

Other basins in the study are the Piceance Basin in Garfield County in western Colorado, and two in southern Colorado: the Raton and the San Juan basins.

“The nifty thing about this as far as looking at a study of the four different basins is that they are three different kinds of oil and gas basins,” Ryan said. “Out here in the Front Range, we’ve got oil and gas; in western Colorado we’ve just got dry gas, in other words, there’s no oil, no liquids; and then down south it’s natural gas that’s coming out of coal beds below the surface.”

The task force is funded for another year and nine months, but the team is not waiting around to start sharing its data. Already they have given conference presentations and been published in peer-reviewed journal publications and are eager to make the information more broadly accessible through a data portal on the network’s website, www.airwatergas.org.

“Over the last part of this project, our goal is to get out information to the public at different levels, not just through academic publications,” Ryan said. The network will engage stakeholders, municipalities, the state, and beyond. “We’ve got some national level efforts that really focus on how we can better manage all the data that’s coming out of all the studies.”

They also plan to share the knowledge at the local, educational level, working with schools and teachers.