Classroom in the sky: CU’s 10,000-foot Mountain Research Station turns 100

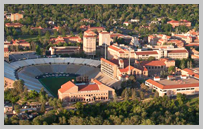

CU Boulder is well-known for its gorgeous campus, with views of the Flatirons, historic buildings and shady canopies of beloved trees. But many have no idea that campus gets even more beautiful as it approaches 10,000 feet.

Twenty-six miles to the west of Boulder, on a 9,500-foot hillside surrounded by dozens of species of flowers and animals, scientists and students at the Mountain Research Station have gathered since 1920 to conduct some of the world’s most unique studies on high-altitude ecology and, more recently, how climate change is altering it.

Today, the station maintains the longest continuous record of greenhouse gas measurements in the continental U.S. and is the highest elevation climate station in the country.

As it celebrates its 100th anniversary this month, its director is already planning for the next 100.

“I’m excited to maintain the gold standard of impactful and internationally recognized alpine research at the station but also think about ways to make it more accessible and raise awareness for the CU community to use it and appreciate it,” said Scott Taylor, director of the Mountain Research Station and assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

To celebrate its centennial the station will host a two week, in-person seminar series in June featuring talks from local artists and scientists over dinner at the newly renovated Wildrose Dining Hall, the oldest building at the station. Part of the proceeds will go toward building a fund to offset the costs of field courses, which are more expensive than on-campus courses, for low-income students.

“To make the field station more inclusive and accessible, providing some of these experiences at reduced costs is really important,” said Taylor.

100 years on Niwot Ridge

The Mountain Research Station, originally known as Science Lodge and Science Camp, was built in 1920, relocated from a field station established in 1908 by Professor Frances Ramaley, just south on the Peak to Peak Highway near the town of Tolland. The first field courses were offered the next year, and the dining hall was built in 1922.

The station was built on property purchased from the U.S. Forest Service. There, it thrived as an educational site, a place for local recreation and some research.

It wasn't until John Marr joined CU Boulder as a faculty member in 1946 that ecology took off as the core focus, according to Bill Bowman, former director of the station and retired professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

“You can't talk about the Mountain Research Station or any of the research up here without mentioning John Marr,” said Bowman. “Marr brought modern ecology to the Front Range.”

Marr founded the Front Range climate and ecology programs which eventually provided the scientific groundwork for the current Niwot Ridge Long-Term Ecological Research Program (LTER) funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). He also founded the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Ecology in 1951, which was renamed the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) in 1967.

From the 1950s until the start of the Niwot Ridge LTER program in 1980, the station grew in its reputation as a prime place to study mountain ecology, not just regionally, but internationally. It drew scientists from around the world researching biology, permafrost, geomorphology and even archaeology.

From 1991 to 2021, Bowman brought additional stability to the station by updating many of its historic buildings, running an NSF-funded summer research experience for undergraduates for two decades and strengthening its connections with CU Boulder and the local community.

Contributions to science and climate research

Serving as a research proxy for Rocky Mountain National Park to the north, the station provides not only an understanding of how the mountains we love to live and play in are affected by environmental change, but how those changes influence our water supply, water quality and much more, said Bowman.

“The legacy of environmental research at the MRS and Niwot Ridge is incredibly valuable. Field stations allow you a long-term view of how things are changing through time,” said Bowman.

The core of the research that takes place at the Mountain Research Station is conducted through the Niwot Ridge LTER, one of the original six NSF-funded long-term ecological research sites out of 28 in the country. The station also runs the Mountain Climate Program, established in 1952, which provides long-term climate data to the LTER and other research projects run through the station, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) atmospheric chemistry program and the National Science Foundation's National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON).

The research station also hosts formal undergraduate and graduate field courses in biology, geography and geology, including some run through other universities. More than 480 scientific papers have been published as a result of faculty and student-led research at the station.

This impressive century of research provides an outstanding knowledge of mountain ecology, hydrology, and soils, and this long-term field data will help scientists also track future changes to mountain ecosystems and the implications of climate change, said Taylor.

The future is visible, inclusive and accessible

Bowman stresses that the station’s success is deeply rooted in all the people who have made it possible—and who will continue to determine its future.

This includes staff and technicians, like station manager Kris Hess, lead climate technician Jen Morse, and Taylor, who succeeded Bowman in June 2021.

“He is uniquely qualified for the position,” said Bowman.

Taylor’s vision for the station includes not only recruiting a wider variety of students to participate in field research, but also making those opportunities affordable, accessible and welcoming—especially for groups of people who have historically been excluded from field work and research. As students’ experiences in the field are often key in their decision to pursue environmental science careers, who gets included in this type of research today can impact who become the leaders of tomorrow.

“I want to make it a more welcoming place in every way—from the courses we offer, to the way that we train researchers and think about field safety, to the buildings we use,” said Taylor. “Being very intentional about who's involved is so important for providing equal opportunities for undergrads to get involved in really meaningful research.”

Many field stations also simply suffer from a lack of visibility, said Taylor. They’re tucked away in the mountains or in remote locations where the community may not know they exist or how to get involved. When he talks to members of the Boulder community about the station, a lot of people don't recognize what he’s talking about.

He wants that to change.

“I'd rather it not be hidden, but instead be a very obvious and celebrated gem, because it is such an important place, and so much important work has gone on there and has the potential to continue there,” said Taylor.